Chemical marine pollution can cause many disturbances which, in the shorter or longer term, can have a negative impact on the economy. These effects may be related to living organisms, ecosystems as well as humans and their activities.

The methods used to assess economic impact distinguish all that is of commercial value from all that is not.

Resources of commercial value of can easily be calculated as they cover all that can be invoiced. An example of this is a professional fishing ban due to intoxication of fish flesh or due to a decrease in tourism in the incident area.

Resources of non-commercial value are difficult to calculate as they cover all that cannot be invoiced. Some examples of this are a ban on recreational shellfish collection, sterility in certain mammals or damages caused to protected areas.

The other difficulty often encountered when assessing economic impact is the lack of relative data for the reference condition, i.e. before the pollution. For instance, in many countries, there is no water quality control network. The quantity of the substance normally present in the environment is unknown, making it impossible to compare this with the quantity found in the polluted water.

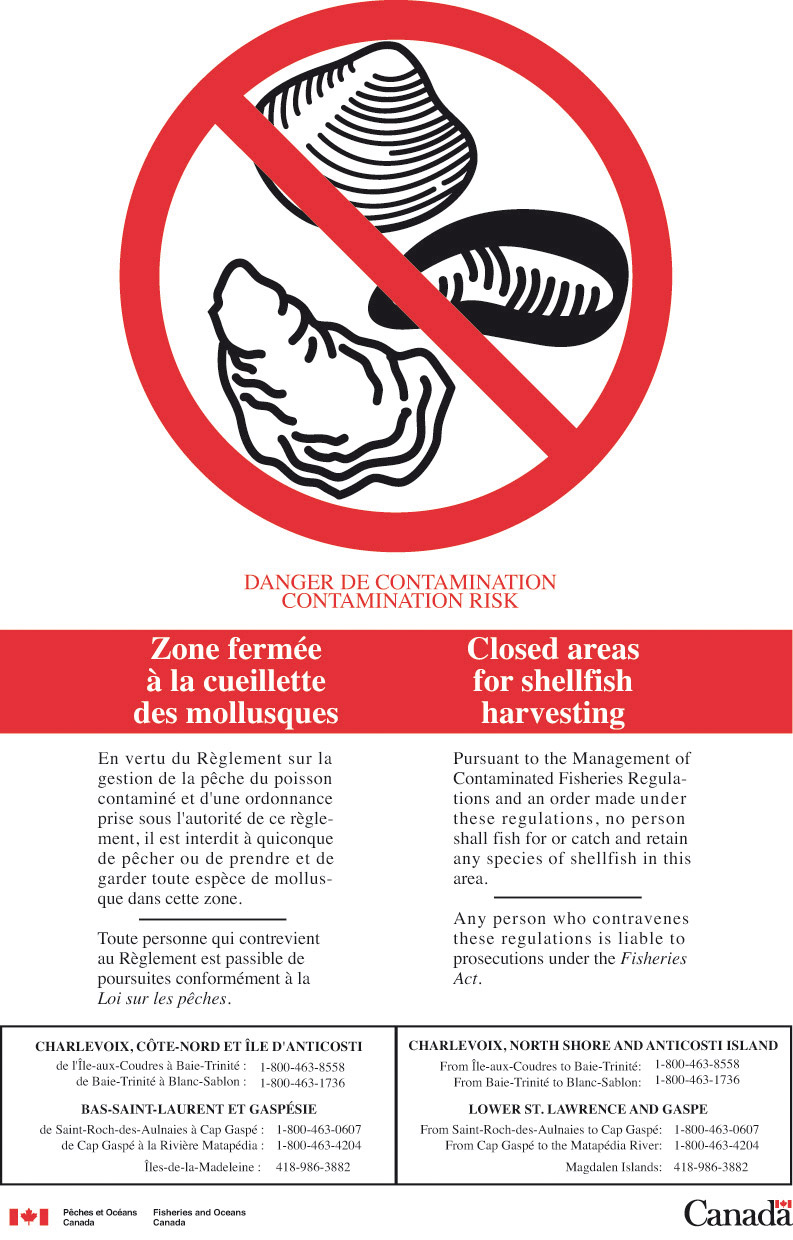

Certain countries are beginning to set up systems to obtain data on the reference condition of the natural environment. In Canada for example, three federal government agencies work together to run the Canadian Shellfish Sanitation Program: Environment and Climate Change Canada, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency and Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

This program detects any aquatic contamination and is the basis for imposing shellfish harvesting bans in the concerned areas where necessary. Once analyses indicate that the pollution has disappeared, the area can be reopened to the public.

Today, there is no worldwide comprehensive mechanism providing for compensation for damage caused that includes the cost of cleaning and restoring the environment. This is why the HNS Convention was created. This is why the HNS Convention was created, and once it enters into force, it will fill a gap in the global framework of liability and compensation conventions.

HNS Convention

The 2010 HNS Convention deals with the liability and compensation for damages caused by HNS transport at sea. This includes both bulk and packaged goods carried by ship.

The types of damages covered are: personal injury and/or loss of life, damage to property, economic loss due to HNS pollution, as well as the cost of environmental protection and restoration. All individuals, companies, local and national authorities of a country that has ratified the Convention can claim compensation. The HNS Convention has been ratified by 7 states – Canada, Denmark, Estonia, Norway, South Africa, Türkiye and France. The HNS Convention will come into force internationally 18 months after 12 states that receive significant quantities of HNS have ratified.

The Special Drawing Right (SDR) was created by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in 1969 to replace monetary gold in major international transactions. Its value is based

on 4 major currencies (US dollar, euro, British pound and Japanese yen).

At the begining of 2016, for instance, one SDR was worth US$1.39.

The HNS Convention provides for the establishment of a two-tier compensation system:

"The HNS Convention – why it is needed", a brochure produced by the International Maritime Organization (IMO), featuring clear and simple diagrams, which encourages States to sign the Convention in order that it be enter into force.

Last update: 05/01/2024